Self-Doubt, Self-Sabotage & No Edit Button

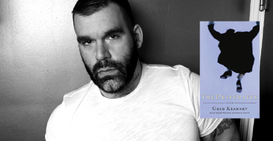

BOOKS: Greg Kearney’s cast of lovable losers will make your head spin and heart break

Story by Gordon Bowness

In Toronto, Nov 2013

As a fiction writer, Greg Kearney is a Tourette’s-addled savant. His deluded, narcissistic characters say and think every inappropriate comment that’s ever darkened your mind, and, I’m sure, quite a few that haven’t.

A writer of short stories, some very, very short, and winner of the ReLit prize for the 2011 collection Pretty, Kearney expands his off-kilter creative palette with his first novel, The Desperates, out this month from Cormorant Books. It’s a jaw-dropping debut, a thrilling, confounding page-turner.

Opening in 1998 Toronto, the hunched-over spine of the novel is the story of Joel, a shell-shocked and baffled 19-year-old fresh off the boat from the remote northwest Ontario town of Kenora. A virgin with questionable hygiene, Joel has no job and no vocation, save some very vague notion that he’s a poet. He is plagued by an inner voice that never shuts up, that constantly criticizes him and those he meets. Even the most mundane of choices swell into morality plays of epic proportions; he swoons with imagined tragedies and sublimities. Joel’s ineptitude, social and sexual, will leave you laughing out loud.

His first day working at a phone-sex line finds Joel confronted by a breathy caller requesting CBT. “CBT? Cognitive Behavioural Therapy?” Joel responds. “I don’t know if this is the right line to be calling for that, although I did that for a few months in grade eight. Didn’t really do much for me, but I didn’t really give over to the process, so….” The caller wants cock and ball torture.

A world where cognitive behavioural therapy and cock and ball torture bump against each other with equal emotional weight is quintessential Kearney. He has been mining the singular realities of an incongruous world for years (I was one of his editors at Xtra where he had a humour column from 1999 to 2005).

After a number of hilariously mortifying incidents in Toronto, Joel heads back to Kenora. His mother, Teresa, the only person he’s ever really connected with, is dying fast of cancer. She, too, says and thinks inappropriate things. Her dying wish is to sleep with the town’s mayor as a way of wreaking revenge on his wife, the mother of a boy who once bullied Joel. But Teresa has last-minute doubts: she’s wearing a clownish cancer wig and can barely stand from painkillers.

“What grownup woman—a wife and mother! a composter!—makes it her dying wish to fuck up somebody’s marriage because they said something mean? Why couldn’t she rise above?,” she asks herself. “Better to be a vengeful person who finishes what she starts than be a radiant person who doesn’t do anything.”

“The story of Joel and his mother definitely contains some autobiography, if only in the particulars,” says Kearney. The Toronto-based author, 40, was born in Kenora. His mother died in 1997. “I had been devoid of life skills and my life had sort of imploded in Toronto. And that dovetailed with my mum being diagnosed with terminal cancer. So I just packed up and helped her through the palliative stages. But my mother wasn’t as plucky and headstrong as Teresa. My mother moved meekly to her death. Teresa is dragged screaming to hers.”

Growing up gay in a rough northern town is one thing; growing up Greg Kearney is something else. He uses words like “hinterland,” “austere” and “stultifying” to describe the Kenora of his childhood. “Natural wonders were lost on me.

“I was hugely effeminate, very ornately effeminate, very particularly effeminate, like how much I was really into Sandy Dennis. That was painful. And my parents, who were deeply blue-collar, were confounded by me.

“According to my Facebook cronies who’ve chosen to stay in Kenora,” he says, “the town hasn’t really evolved. Or it may have been evolved the whole time and I just had such phobic blinders on that I never actually saw it.

“I was kind of an hysterical, erratic child. I was out to myself so early that even as a preteen I’d begun the systematic process of shutting down. So even if there were any kind of queer allies or nourishing experience [in Kenora] I wouldn’t have known because I was so pathologically inward.”

Whether self-imposed or not, the gulf between Kearney and his environment cracked wide open with the death of his older sister when he was only six. “It turned me into an artist—that moment,” he says. “I think I was playing with the rubber rim off a mason jar in the driveway when I heard my mother scream over the phone that my sister had been hit by a car. And instantly after that, if I wasn’t already, I was turned into a perpetual observer.” In Kearney’s case, that perennially queer, bifurcated perspective has always skewed to the macabre. “Even as a small child I was aware of terminal illness and the process of dying, acutely aware of mortality at every turn.”

Death stalks The Desperates: a beloved babysitter chokes on a hotdog, a mother’s mesothelioma, a lover dead from AIDS—which brings us to the novel’s third main character, Edmund. He offers an intriguing counterpoint to Joel and Teresa. Edmund is wise and accomplished. But he’s just as lost. He’s an AIDS survivor who is barely surviving. Edmund spends his days listening to his empty, silent house. His lover died of AIDS years prior and Edmund fully expected to follow him to an early grave. But he didn’t. Because of then new antiretroviral drugs, Edmund rises from his deathbed to find a life devoid of purpose, meaning and friendship. Until he finds drugs, specifically meth.

“There’s such a gap in AIDS literature,” says Kearney. “It all stops around 1992—Mark Doty, Paul Monette. So nobody covers this incredibly dynamic switch in ’96 [with the introduction of antiretroviral drugs] when people who were dying suddenly were not. And so many of them who have lived have not known what to do with themselves.”

Despite the comedic situations that Kearney is so adept at inventing, his characters ring true. “All of Edmund’s narrative I’ve been privy to in my sexual adventures,” says Kearney. “I mean, I’m a huge fan of group sex and I’ve observed that milieu of men intimately and often. The PNP [party and play] crowd, and me as the lone sober person… it was such grist.”

Given its strengths, what makes The Desperates even more amazing is that Kearney completed it after being diagnosed with an HIV-related neurocognitive disorder. His short-term memory is shot. “I’m on disability and dealing with that. And dealing with not trusting the durability of my health. It’s a nervous, enervating state. So I’m very familiar with [Edmund’s] nether world.” Kearney says it’s crucial to be open about his current health issues. “That’s the reality of HIV in the 21st century. There are still huge physical and emotional challenges that no one is talking about.”

In the book, Kearney characterizes the PNP scene as bereft of true connection. But some outrageous characters drift through this emotional limbo. Edmund is introduced to meth by Binny, a kid he picks up in a bar, a scrawny hustler with “a fist of a face, wind-burned and blunt, with small, spiteful grey eyes and a tight, angled mouth, like a hasty hem.” Binny lives only for the now; he makes sense of a tough life solely through the songs and one-line bios of female pop stars. “I’ve been beaten and raped and stabbed and left for dead,” says Binny in one of his distinctive refrains, “but I am a soul survivor, like Diva Tina, Wildest Dreams Tour presented by Hanes Pantyhose realness. So it is all good.” The book is peppered with Binny’s mind-boggling riffs on pop diva “realness.” His character reveals Kearney, a self-described “singer/songwriter hoarder,” at his demented, memory-challenged, unexpurgated best.

Self-sabotage is a recurring theme in The Desperates. Self-doubt, second-guessing, ever-shifting life goals… Kearney’s characters rarely get it together. But they are churning with need, always striving and seldom mean. They’re lovable.

The Desperates is an exceptional novel by one of Canada’s most unique literary voices.

THE DESPERATES Cormorant Books, $21.95

Story by Gordon Bowness

In Toronto, Nov 2013

As a fiction writer, Greg Kearney is a Tourette’s-addled savant. His deluded, narcissistic characters say and think every inappropriate comment that’s ever darkened your mind, and, I’m sure, quite a few that haven’t.

A writer of short stories, some very, very short, and winner of the ReLit prize for the 2011 collection Pretty, Kearney expands his off-kilter creative palette with his first novel, The Desperates, out this month from Cormorant Books. It’s a jaw-dropping debut, a thrilling, confounding page-turner.

Opening in 1998 Toronto, the hunched-over spine of the novel is the story of Joel, a shell-shocked and baffled 19-year-old fresh off the boat from the remote northwest Ontario town of Kenora. A virgin with questionable hygiene, Joel has no job and no vocation, save some very vague notion that he’s a poet. He is plagued by an inner voice that never shuts up, that constantly criticizes him and those he meets. Even the most mundane of choices swell into morality plays of epic proportions; he swoons with imagined tragedies and sublimities. Joel’s ineptitude, social and sexual, will leave you laughing out loud.

His first day working at a phone-sex line finds Joel confronted by a breathy caller requesting CBT. “CBT? Cognitive Behavioural Therapy?” Joel responds. “I don’t know if this is the right line to be calling for that, although I did that for a few months in grade eight. Didn’t really do much for me, but I didn’t really give over to the process, so….” The caller wants cock and ball torture.

A world where cognitive behavioural therapy and cock and ball torture bump against each other with equal emotional weight is quintessential Kearney. He has been mining the singular realities of an incongruous world for years (I was one of his editors at Xtra where he had a humour column from 1999 to 2005).

After a number of hilariously mortifying incidents in Toronto, Joel heads back to Kenora. His mother, Teresa, the only person he’s ever really connected with, is dying fast of cancer. She, too, says and thinks inappropriate things. Her dying wish is to sleep with the town’s mayor as a way of wreaking revenge on his wife, the mother of a boy who once bullied Joel. But Teresa has last-minute doubts: she’s wearing a clownish cancer wig and can barely stand from painkillers.

“What grownup woman—a wife and mother! a composter!—makes it her dying wish to fuck up somebody’s marriage because they said something mean? Why couldn’t she rise above?,” she asks herself. “Better to be a vengeful person who finishes what she starts than be a radiant person who doesn’t do anything.”

“The story of Joel and his mother definitely contains some autobiography, if only in the particulars,” says Kearney. The Toronto-based author, 40, was born in Kenora. His mother died in 1997. “I had been devoid of life skills and my life had sort of imploded in Toronto. And that dovetailed with my mum being diagnosed with terminal cancer. So I just packed up and helped her through the palliative stages. But my mother wasn’t as plucky and headstrong as Teresa. My mother moved meekly to her death. Teresa is dragged screaming to hers.”

Growing up gay in a rough northern town is one thing; growing up Greg Kearney is something else. He uses words like “hinterland,” “austere” and “stultifying” to describe the Kenora of his childhood. “Natural wonders were lost on me.

“I was hugely effeminate, very ornately effeminate, very particularly effeminate, like how much I was really into Sandy Dennis. That was painful. And my parents, who were deeply blue-collar, were confounded by me.

“According to my Facebook cronies who’ve chosen to stay in Kenora,” he says, “the town hasn’t really evolved. Or it may have been evolved the whole time and I just had such phobic blinders on that I never actually saw it.

“I was kind of an hysterical, erratic child. I was out to myself so early that even as a preteen I’d begun the systematic process of shutting down. So even if there were any kind of queer allies or nourishing experience [in Kenora] I wouldn’t have known because I was so pathologically inward.”

Whether self-imposed or not, the gulf between Kearney and his environment cracked wide open with the death of his older sister when he was only six. “It turned me into an artist—that moment,” he says. “I think I was playing with the rubber rim off a mason jar in the driveway when I heard my mother scream over the phone that my sister had been hit by a car. And instantly after that, if I wasn’t already, I was turned into a perpetual observer.” In Kearney’s case, that perennially queer, bifurcated perspective has always skewed to the macabre. “Even as a small child I was aware of terminal illness and the process of dying, acutely aware of mortality at every turn.”

Death stalks The Desperates: a beloved babysitter chokes on a hotdog, a mother’s mesothelioma, a lover dead from AIDS—which brings us to the novel’s third main character, Edmund. He offers an intriguing counterpoint to Joel and Teresa. Edmund is wise and accomplished. But he’s just as lost. He’s an AIDS survivor who is barely surviving. Edmund spends his days listening to his empty, silent house. His lover died of AIDS years prior and Edmund fully expected to follow him to an early grave. But he didn’t. Because of then new antiretroviral drugs, Edmund rises from his deathbed to find a life devoid of purpose, meaning and friendship. Until he finds drugs, specifically meth.

“There’s such a gap in AIDS literature,” says Kearney. “It all stops around 1992—Mark Doty, Paul Monette. So nobody covers this incredibly dynamic switch in ’96 [with the introduction of antiretroviral drugs] when people who were dying suddenly were not. And so many of them who have lived have not known what to do with themselves.”

Despite the comedic situations that Kearney is so adept at inventing, his characters ring true. “All of Edmund’s narrative I’ve been privy to in my sexual adventures,” says Kearney. “I mean, I’m a huge fan of group sex and I’ve observed that milieu of men intimately and often. The PNP [party and play] crowd, and me as the lone sober person… it was such grist.”

Given its strengths, what makes The Desperates even more amazing is that Kearney completed it after being diagnosed with an HIV-related neurocognitive disorder. His short-term memory is shot. “I’m on disability and dealing with that. And dealing with not trusting the durability of my health. It’s a nervous, enervating state. So I’m very familiar with [Edmund’s] nether world.” Kearney says it’s crucial to be open about his current health issues. “That’s the reality of HIV in the 21st century. There are still huge physical and emotional challenges that no one is talking about.”

In the book, Kearney characterizes the PNP scene as bereft of true connection. But some outrageous characters drift through this emotional limbo. Edmund is introduced to meth by Binny, a kid he picks up in a bar, a scrawny hustler with “a fist of a face, wind-burned and blunt, with small, spiteful grey eyes and a tight, angled mouth, like a hasty hem.” Binny lives only for the now; he makes sense of a tough life solely through the songs and one-line bios of female pop stars. “I’ve been beaten and raped and stabbed and left for dead,” says Binny in one of his distinctive refrains, “but I am a soul survivor, like Diva Tina, Wildest Dreams Tour presented by Hanes Pantyhose realness. So it is all good.” The book is peppered with Binny’s mind-boggling riffs on pop diva “realness.” His character reveals Kearney, a self-described “singer/songwriter hoarder,” at his demented, memory-challenged, unexpurgated best.

Self-sabotage is a recurring theme in The Desperates. Self-doubt, second-guessing, ever-shifting life goals… Kearney’s characters rarely get it together. But they are churning with need, always striving and seldom mean. They’re lovable.

The Desperates is an exceptional novel by one of Canada’s most unique literary voices.

THE DESPERATES Cormorant Books, $21.95