Grief

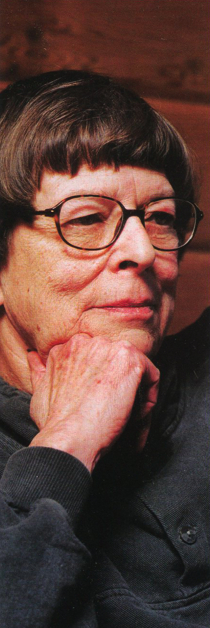

Photograph by Sheila Spence

Photograph by Sheila Spence

Author Jane Rule writes about the death last year of her partner Helen Sonthoff

Go Big, May 2001

When I was young, I had fears about committing myself to a relationship. The first was that I would cut myself off from infinite possibilities. With more experience, I feared that no woman would be willing to take a relationship with me seriously against the demands of a man or any family member who laid realer claim on her loyalty. Then finally I was afraid that commitment would leave me vulnerable to loss of a sort I couldn’t endure.

After I had shared 45 years of living with Helen Sonthofff, she died. The door of life slammed in my face. People writing letters of condolence spoke about dreaming of Helen. She didn’t appear in my dreams for months, and, when she did briefly, she was distressed and damaged, out of reach of my care. I was confronted with what I had exactly dreaded, a grief stupid and numbing. I slept badly and briefly, found eating pointless, and felt appalled that I had no way to access 45 years of good living for any kind of comfort. It was a grief that felt almost a betrayal of the deep joy my life.

Any yet, at the hardest and loneliest hours, I did know that it was a small price for what I might have, as a self-protective youngster, avoided. “The last gift you gave her,” a friend wrote, “was to outlive her.”

Learning to survive is, at first, simply a series of distractions which begin with a love/hate relationship with everything Helen loved, from daffodils to children's laughter, from Christmas to lima beans.

I don't now try to make sense of that loss. I learn to make use of it instead. The house I prepared for Helen's broken hip, to which she never returned, now shelters a friend badly hurt in a car accident, a friend about whom Helen used to say, “Just seeing her face makes me feel better.” It does me, too.

Risk, grow, grieve. Helen's like will not walk this earth again, nor I love like that again, but the care I learned is useful still for all she and I learned to love together.

Go Big, May 2001

When I was young, I had fears about committing myself to a relationship. The first was that I would cut myself off from infinite possibilities. With more experience, I feared that no woman would be willing to take a relationship with me seriously against the demands of a man or any family member who laid realer claim on her loyalty. Then finally I was afraid that commitment would leave me vulnerable to loss of a sort I couldn’t endure.

After I had shared 45 years of living with Helen Sonthofff, she died. The door of life slammed in my face. People writing letters of condolence spoke about dreaming of Helen. She didn’t appear in my dreams for months, and, when she did briefly, she was distressed and damaged, out of reach of my care. I was confronted with what I had exactly dreaded, a grief stupid and numbing. I slept badly and briefly, found eating pointless, and felt appalled that I had no way to access 45 years of good living for any kind of comfort. It was a grief that felt almost a betrayal of the deep joy my life.

Any yet, at the hardest and loneliest hours, I did know that it was a small price for what I might have, as a self-protective youngster, avoided. “The last gift you gave her,” a friend wrote, “was to outlive her.”

Learning to survive is, at first, simply a series of distractions which begin with a love/hate relationship with everything Helen loved, from daffodils to children's laughter, from Christmas to lima beans.

I don't now try to make sense of that loss. I learn to make use of it instead. The house I prepared for Helen's broken hip, to which she never returned, now shelters a friend badly hurt in a car accident, a friend about whom Helen used to say, “Just seeing her face makes me feel better.” It does me, too.

Risk, grow, grieve. Helen's like will not walk this earth again, nor I love like that again, but the care I learned is useful still for all she and I learned to love together.