War Child

NEW FICTION: A searing, surreal journey from Sarajevo to Toronto

In Toronto, May 2014

Review by Gordon Bowness

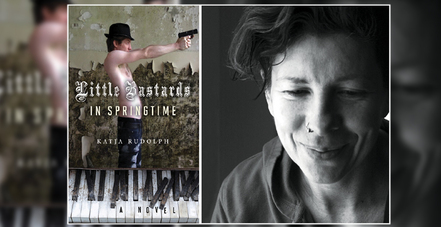

Humans are resilient creatures, none more so than our young. Children have an incredible capacity for survival. Violence, disease, hunger… kids keep on living. And that’s the terrifying truth explored unflinchingly by Toronto writer Katja Rudolph in her debut novel Little Bastards in Springtime. The young can survive almost anything, suggests Rudolph, except perhaps betrayal.

Little Bastards is told from the point of view of Jevrem Andric, a happy, inquisitive youth growing up in Sarajevo prior to and during the Bosnian War of the 1990s. Jevrem’s father, a journalist, is a Serb; his mother, a concert pianist, is a Croat.

Jevrem’s grandmother, his “Baka,” is a former communist partisan who fought fascists during World War II. The family embodies the multicultural and humanist ideals of Yugoslavia. But rising nationalism and constitutional crises follow the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite regimes. Secession and violence splinter Yugoslavia as ethnic minorities try to carve out new majority homelands, and each new homeland creates different sets of minorities. Besieged on all sides, with Serbian militia in the hills surrounding Sarajevo and Bosniak militia in the streets, Jevrem’s family watch dismayed as hundreds of years of multiethnic cohabitation and culture evaporate. They have nowhere to hide, yet they refuse to leave. Ultimately young Jevrem is betrayed: His loving, well-intentioned family fails to protect him from the horrors of war. One moment the 11-year-old is happily playing soccer with friends who are a mixed bag of ethnicities and religions. The next moment he’s wondering why his father’s relatives, the Serbian side of the family, no longer visit. Then he’s dodging bullets in the streets.

Rudolph has a wonderful way of rendering the inchoate feelings and mixed-up thoughts of a confused man-child like Jevrem. In his world, stories, dreams and memories pile up, existing cheek by jowl. The telling becomes surreal at times, in part because of the unreal nature of war, in part because of Jevrem’s yearning, his emotional grasping, that reaches out far beyond his comprehension.

The depiction of a proudly liberal and diverse city like Sarajevo slowly becoming a war zone is particularly chilling in its seeming inevitability, how little changes begin to snowball out of control. The power of ethnic and religious identities in times of violent unrest, the retreat into murderous clans and tribes, is horrifying to behold, especially since it echoes what’s happening currently in Ukraine and elsewhere.

This powerful debut falters only occasionally. Rudolph, a political theorist, has young Jevrem digest and recount some highfalutin’ conversations about geopolitics and sociology. (Granted these asides provide fascinating background exposition for those unfamiliar with the region’s turbulent history.) But every time I catch a whiff of didacticism or begin to doubt the vocabulary of 11-year-old or 16-year-old Jevrem, Rudolph spins the frame: This is a book bursting with incident. Jevrem’s mind is always a whir; he is always on the go. And he takes the reader with him. It’s an audacious accomplishment: seducing us to empathize with a damaged war refugee, someone easily dismissed as just another drug-addled macho thug, a lost child, a mistake of history.

The last two thirds of the book concern Jevrem’s troubled life in Toronto, where what’s left of his family emigrates after the war. Jevrem, now 16, leads a small band of teenagers, other Yugoslavian refugees, known as the Bastards, who rob and terrorize students, neighbours and strangers at will, for kicks as much as for loot. All the well-meaning do-gooders and guidance counsellors—and liberal multicultural Toronto itself— offer cold comfort to a screwed- up kid like Jevrem. And yet there is a core of good in him. One lyrical moment finds Jevrem stealing a van and breaking into a swimming pool with steam rooms so a street drunk and her friends can bathe. Jevrem’s behaviour becomes increasingly erratic; something’s got to give. But every choice he makes seems to take him further from any hope of redemption, any chance at freedom.

Trapped in a juvenile correction facility, with adult prison time looming, Jevrem makes one last desperate move. That Rudolph is able to end his story on a credibly hopeful note is one last remarkable conjuring trick in a bravura display of fiction writing.

LITTLE BASTARDS IN SPRINGTIME. Katja Rudolph. Harper Collins. $29.99. Releases May 27.

In Toronto, May 2014

Review by Gordon Bowness

Humans are resilient creatures, none more so than our young. Children have an incredible capacity for survival. Violence, disease, hunger… kids keep on living. And that’s the terrifying truth explored unflinchingly by Toronto writer Katja Rudolph in her debut novel Little Bastards in Springtime. The young can survive almost anything, suggests Rudolph, except perhaps betrayal.

Little Bastards is told from the point of view of Jevrem Andric, a happy, inquisitive youth growing up in Sarajevo prior to and during the Bosnian War of the 1990s. Jevrem’s father, a journalist, is a Serb; his mother, a concert pianist, is a Croat.

Jevrem’s grandmother, his “Baka,” is a former communist partisan who fought fascists during World War II. The family embodies the multicultural and humanist ideals of Yugoslavia. But rising nationalism and constitutional crises follow the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellite regimes. Secession and violence splinter Yugoslavia as ethnic minorities try to carve out new majority homelands, and each new homeland creates different sets of minorities. Besieged on all sides, with Serbian militia in the hills surrounding Sarajevo and Bosniak militia in the streets, Jevrem’s family watch dismayed as hundreds of years of multiethnic cohabitation and culture evaporate. They have nowhere to hide, yet they refuse to leave. Ultimately young Jevrem is betrayed: His loving, well-intentioned family fails to protect him from the horrors of war. One moment the 11-year-old is happily playing soccer with friends who are a mixed bag of ethnicities and religions. The next moment he’s wondering why his father’s relatives, the Serbian side of the family, no longer visit. Then he’s dodging bullets in the streets.

Rudolph has a wonderful way of rendering the inchoate feelings and mixed-up thoughts of a confused man-child like Jevrem. In his world, stories, dreams and memories pile up, existing cheek by jowl. The telling becomes surreal at times, in part because of the unreal nature of war, in part because of Jevrem’s yearning, his emotional grasping, that reaches out far beyond his comprehension.

The depiction of a proudly liberal and diverse city like Sarajevo slowly becoming a war zone is particularly chilling in its seeming inevitability, how little changes begin to snowball out of control. The power of ethnic and religious identities in times of violent unrest, the retreat into murderous clans and tribes, is horrifying to behold, especially since it echoes what’s happening currently in Ukraine and elsewhere.

This powerful debut falters only occasionally. Rudolph, a political theorist, has young Jevrem digest and recount some highfalutin’ conversations about geopolitics and sociology. (Granted these asides provide fascinating background exposition for those unfamiliar with the region’s turbulent history.) But every time I catch a whiff of didacticism or begin to doubt the vocabulary of 11-year-old or 16-year-old Jevrem, Rudolph spins the frame: This is a book bursting with incident. Jevrem’s mind is always a whir; he is always on the go. And he takes the reader with him. It’s an audacious accomplishment: seducing us to empathize with a damaged war refugee, someone easily dismissed as just another drug-addled macho thug, a lost child, a mistake of history.

The last two thirds of the book concern Jevrem’s troubled life in Toronto, where what’s left of his family emigrates after the war. Jevrem, now 16, leads a small band of teenagers, other Yugoslavian refugees, known as the Bastards, who rob and terrorize students, neighbours and strangers at will, for kicks as much as for loot. All the well-meaning do-gooders and guidance counsellors—and liberal multicultural Toronto itself— offer cold comfort to a screwed- up kid like Jevrem. And yet there is a core of good in him. One lyrical moment finds Jevrem stealing a van and breaking into a swimming pool with steam rooms so a street drunk and her friends can bathe. Jevrem’s behaviour becomes increasingly erratic; something’s got to give. But every choice he makes seems to take him further from any hope of redemption, any chance at freedom.

Trapped in a juvenile correction facility, with adult prison time looming, Jevrem makes one last desperate move. That Rudolph is able to end his story on a credibly hopeful note is one last remarkable conjuring trick in a bravura display of fiction writing.

LITTLE BASTARDS IN SPRINGTIME. Katja Rudolph. Harper Collins. $29.99. Releases May 27.