Common-law Breakers

ISSUES: The Supreme Court de-legitimizes the relationships of 1.2 million Quebeckers prompting family law experts to ask: Is Charter of Rights and Freedoms dead?

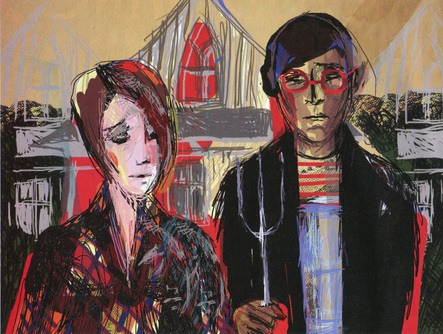

Story by Gordon Bowness • Illustration by John Webster

In Toronto, March 2013

The legal ground is shifting violently underneath our conjugal beds.

When Canada legalized same-sex marriage in 2005, it was never meant to make weddings mandatory. Rather, it was simply supposed to be the final word on equality in relationships. But a recent Supreme Court ruling highlights the fact that many gay men and lesbians who have not formalized their relationships could find themselves out in the cold once again, together with millions of unmarried women.

Even more chilling, the Supreme Court's January ruling could have a devastating effect on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, returning the country to a time when provinces were allowed to discriminate openly against minorities.

Most Canadians wrongly assume that common-law couples — whether gay or straight — enjoy the same rights and obligations as married couples. That misperception was brought into sharp focus with the Supreme Court ruling in January in a case known as Eric v Lola, which affirmed that common-law partners in Quebec have no right to spousal support or to a share in their partner’s property when the relationship ends. The ruling has outraged family law experts for leaving roughly 600,000 Quebec women in common-law relationships with no protection. One expert goes so far as to say the ruling not only de-legitimizes relationships of 1.2 million Quebeckers, it threatens the very nature of Confederation — the fundamental relationship among the provinces and the federal government.

The Supreme Court ruling in Eric v Lola was a split decision; the math is a little wonky. Five of the nine justices — including Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin — agreed that the Civil Code of Quebec was discriminatory toward common-law spouses for not affording them the same protections as married couples; four did not. McLachlin, however, “saved” the legislation on the grounds that the discrimination was justified under Section 1 of the Charter, which states that a law may infringe on Charter rights if it can be demonstrably justified as reasonable in a free and democratic society. The four justices who found no discrimination didn’t find it necessary to address Section 1. Somehow their four votes on the question of discrimination and the chief justice’s one vote on Section 1 added up to a majority.

“Even if the infringement can be justified, for example, limiting tobacco companies from advertising freely, such infringement must be a ‘minimal impairment’ for the discriminated group,” says Montreal lawyer Anne-France Goldwater who, along with Marie-Hélène Dubé, her partner at Goldwater, Dubé, represented Lola in her first two court appearances (but not at the Supreme Court). “Yet common-law spouses have no protection in Quebec. How can this be a minimal impairment? The Chief Justice didn't even blink on this point.”

“The decision shows that there is no consensus in the court on the issues,” says Toronto lawyer Kelly Jordan, partner at Jordan Battista. “And only a bare majority found that the legislation discriminated against common-law couple, which is surprising.”

Goldwater worries that allowing Quebec the freedom to discriminate strikes at the very heart of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a precedent that could go way beyond this one case.

“It’s very, very rare for the Supreme Court to save a law that’s held to be discriminatory,” says Goldwater. “The Chief Justice’s justification for that is Quebec, being Quebec, is free to discriminate.

“This leaves constitutional law in an unexpected tension: As long as a provincial government wants to discriminate, it now appears to be free to do so. This is an intolerable proposition that nobody has actually noticed or commented upon.”

Goldwater argues that Eric v Lola turns the clock back to 1995, the year of the problematic Egan case. That’s when the Supreme Court ruled that denying Old Age Security spousal benefits to a gay couple was discriminatory — the first time that sexual orientation was read into the Charter's anti-discriminaion clause — but that the discrimination was allowed under Section 1. That’s why Goldwater finds Eric V Lola so disturbing. It’s as if Vriend never happened. In that 1998 case the Supreme Court ruled that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation could not be justified under Section 1 of the Charter, a key decision en route to securing same-sex marriage.

“Vriend is one of the most important cases ever written,” says Goldwater. “When Alberta discriminated against gays by deliberately refusing to protect them in Vriend, the Supreme Court had a fit and blasted Alberta. But in Eric v Lola, where Quebec discriminated against common-law couples by deliberately refusing to protect them, the Supreme Court handed them a cigar.

“It’s like throwing constitutional law back like 20 years.”

Goldwater uses terms like “politicized” and Quebec “appeasement” to criticize the Chief Justice’s ruling. “If the Chief Justice has just changed constitutional law in Canada as we know it, I think a majority of judges should say so in the next judgment. Let’s say there has been a delicate wish to avoid offending Quebec, which is something I find unacceptable.

“If the Supreme Court feels that federalism means that everybody has to bow to Quebec’s will, but Quebec has no obligation to cooperate with the rest of Canada, I’m scared for Confederation. I think the Supreme Court owes it to the population to say what the status of Quebec is in Confederation. Are we subject to the Charter anymore or not? I think it’s a pretty critical question.”

The fact that the question has been raised in a family law case is particularly significant for gay men and lesbians across Canada.

One of the reasons we have same-sex marriage federally is that as common-law couples won certain protections courts found it wrong to exclude same-sex couples from those protections. Common-law and same-sex relationships are linked, historically and legally.

“For the longest time, common-law relationships and same-sex relationships were being tested in the courts and were advancing kind of in lockstep as discriminated minorities, in fits and starts, lurching forward,” Goldwater says. She is uniquely positioned to understand that dynamic. Not only is she a leading advocate for the rights of women and mothers in common-law relationships, she and Dubé represented Hendricks and Leboeuf in the 2002 landmark ruling that won same-sex marriage in Quebec.

For observers like Goldwater and Jordan, now that the same-sex marriage fight has been won federally, it seems as if the Supreme Court is pulling up the drawbridge around the institution and leaving common-law couples and other non-traditional families out in the cold.

“I’m worried on a much broader level for the Supreme Court,” says Goldwater. “For lawyers interested in constitutional law, we have the feeling, and it’s very subjective of course, that the Supreme Court seems to be turning away from the liberal tendencies it used to have in the late ’80s and ’90s, which was really pro-Charter litigation. We seem to be in a new era of unexplained timidity.”

That means Charter challenges in family law may be out of bounds in the short to medium term. Future changes — which will need to address everything from assisted reproduction, surrogacy for gay fathers and multiple parents to the application of federal child support guidelines — will have to originate with provincial legislatures and new statues, not the courts. How that will proceed is anyone’s guess. When the Eric v Lola ruling came down, Quebec’s justice minister Bertrand St-Arnaud said the government was open to changing the laws to recognize the rights of common-law spouses. But then came a backlash and the government seems to be backpedaling.

While the wider implications of Eric v Lola remain uncertain, the ruling immediately impacts the relationships of 1.2 million people in Quebec. It also spotlights that common-law couples across the country — despite what they themselves may think — may not hold the same status as their married counterparts. And for all the media attention heaped on same-sex marriage, the vast majority of gay and lesbian couples in Canada are common-law. StatsCan’s latest findings on families show that while the number of same-sex marriages tripled between 2006 and 2011, same-sex common-law couples still outnumber same-sex married couples by more than two to one.

Only in BC (as of this month), Manitoba and Saskatchewan are common-law and married couples treated virtually the same, as well as in areas under federal jurisdictions, like income tax and Old Age Security. The rest is a patchwork, province to province. Confusion reigns.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there,” says Jordan. “A lot of people think they’re common-law after six months to a year. People tend to assume that they have an interest in the home after they’ve been together for so long. But it’s not true. I hear all kinds of things.”

The ruling in Eric v Lola brought to a close an 11-year legal odyssey. (There’s a publication ban in Canada on the parties’ real names. They’re easily found online, however; after all, how many billionaires are there in Quebec?) After meeting in Lola’s home country of Brazil when she was 17, Eric and Lola dated on and off for a few years. Later moving to Quebec, Lola lived with Eric for seven years, during which time they had three children. Lola wanted to get married; Eric didn’t, stating he didn’t believe in it. They broke up in 2002. Lola had custody of the children and Eric agreed to pay child support (and they came to their own agreement on access to the family home). But Lola also claimed spousal support and a share of Eric’s property, filing notice of a Charter challenge that argued de facto spouses (the legal term for common-law couples in Quebec, or conjoints de fait) should have the same rights as married couples when they split. The Quebec Superior Court denied her constitutional claims but the Quebec Court of Appeal allowed her claim for spousal support. That’s the ruling the Supreme Court overturned.

“There are 1.2 million people living common-law in the province of Quebec, about one half of them are presumed to be women, more or less, and they’ve just been left high and dry by the Supreme Court. No protection at all,” says Goldwater. “People almost passed out when they heard the decision. Nobody, but nobody, thought that would be the judgment.”

“I don’t know why we would protect vulnerable spouses who are married and not protect vulnerable spouses who are not married,” says Jordan. “I think as a society as a whole we should protect economically disadvantaged spouses upon dissolution of their relationship, particularly where there are children. That’s what’s so egregious about the facts in the Eric and Lola case.

“For those of us who do family law in the trenches, it’s a really hard decision to swallow,” says Jordan. “It’s one thing on the property, but on the spousal support? It’s just really hard.”

The irony lost on no one is that the ruling comes out of Quebec, where there are more common-law couples than anywhere else in the world. In Quebec, 31.4 percent of all families are common-law (compared to 16.7 percent nationally), and the number is growing.

“Women are in a very vulnerable position in Quebec,” says Jordan. “It’s the only province or territory that doesn’t have spousal support for common-law couples. So they’re really way out there. It’s antiquated.”

In her decision, Chief Justice McLachlin wrote that Quebec’s legal framework was designed “to promote choice and autonomy for all Quebec spouses. “Those who choose to marry choose the protections — but also the responsibilities — associated with that status. Those who choose not to marry avoid these state-imposed responsibilities and protections.”

Critics of the decision argue that choice in common-law relationships often resides solely with the wealthier party. People often stumble into such relationships; sometimes a disadvantaged partner can’t insist on a marriage. As Justice Rosalie Abella wrote in her dissenting opinion, “The decision to live together as unmarried spouses may, for some, not in fact be a choice at all.”

“I don’t think people choose to marry or not to marry based on wanting to enter into a certain legal set of rights and obligations,” says Jordan. “They don’t even understand the difference between common-law and married couples. So I don’t buy this choice argument.”

Whether it was an unmarried woman living and working on her male partner’s farm or a male couple paying into the Canada Pension Plan, case after case outside of Quebec recognized these relationships as marriages in all but name.

“This is the standard in the rest of Canada: You don’t look at whether a couple has gone to a city hall or a church to start their conjugal life. You look at the functional nature of the relationship. If it’s a conjugal, familial relationship, similar to marriage, then you recognize it as such,” says Goldwater.

Or as Abella, the only justice on the Supreme Court with a family law background, wrote in her dissent, “As the history of modern family law demonstrates, fairness requires that we look at the content of the relationship’s social package, not at how it is wrapped.”

But in most parts of Canada, despite winning increasing protections, common-law relationships are still not completely equivalent to marriage. In Ontario, for example, the big disadvantage for common-law couples is in property sharing and estates. Both married and common-law spouses are entitled to spousal support if the relationship breaks down (though only after the three-year time period required to establish a common-law relationship). But only married spouses share equally property accumulated during the marriage. The same holds if your partner dies. If you are not married, you have no automatic claim against your partner’s estate, no matter how long you’ve lived together or even if you have children together.

If you are in a common-law relationship in Ontario, write a will, otherwise you’re leaving your partner in a potentially awful financial and emotional bind. For the immediate future, it seems, even a Charter challenge can’t undo that bind.

LGBT activism has forced huge changes in Canadian family law. But despite the profound victory on same-sex marriage, those battles could be far from over. It will be fascinating to see how LGBT activists might affect those changes in the future. •

Story by Gordon Bowness • Illustration by John Webster

In Toronto, March 2013

The legal ground is shifting violently underneath our conjugal beds.

When Canada legalized same-sex marriage in 2005, it was never meant to make weddings mandatory. Rather, it was simply supposed to be the final word on equality in relationships. But a recent Supreme Court ruling highlights the fact that many gay men and lesbians who have not formalized their relationships could find themselves out in the cold once again, together with millions of unmarried women.

Even more chilling, the Supreme Court's January ruling could have a devastating effect on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, returning the country to a time when provinces were allowed to discriminate openly against minorities.

Most Canadians wrongly assume that common-law couples — whether gay or straight — enjoy the same rights and obligations as married couples. That misperception was brought into sharp focus with the Supreme Court ruling in January in a case known as Eric v Lola, which affirmed that common-law partners in Quebec have no right to spousal support or to a share in their partner’s property when the relationship ends. The ruling has outraged family law experts for leaving roughly 600,000 Quebec women in common-law relationships with no protection. One expert goes so far as to say the ruling not only de-legitimizes relationships of 1.2 million Quebeckers, it threatens the very nature of Confederation — the fundamental relationship among the provinces and the federal government.

The Supreme Court ruling in Eric v Lola was a split decision; the math is a little wonky. Five of the nine justices — including Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin — agreed that the Civil Code of Quebec was discriminatory toward common-law spouses for not affording them the same protections as married couples; four did not. McLachlin, however, “saved” the legislation on the grounds that the discrimination was justified under Section 1 of the Charter, which states that a law may infringe on Charter rights if it can be demonstrably justified as reasonable in a free and democratic society. The four justices who found no discrimination didn’t find it necessary to address Section 1. Somehow their four votes on the question of discrimination and the chief justice’s one vote on Section 1 added up to a majority.

“Even if the infringement can be justified, for example, limiting tobacco companies from advertising freely, such infringement must be a ‘minimal impairment’ for the discriminated group,” says Montreal lawyer Anne-France Goldwater who, along with Marie-Hélène Dubé, her partner at Goldwater, Dubé, represented Lola in her first two court appearances (but not at the Supreme Court). “Yet common-law spouses have no protection in Quebec. How can this be a minimal impairment? The Chief Justice didn't even blink on this point.”

“The decision shows that there is no consensus in the court on the issues,” says Toronto lawyer Kelly Jordan, partner at Jordan Battista. “And only a bare majority found that the legislation discriminated against common-law couple, which is surprising.”

Goldwater worries that allowing Quebec the freedom to discriminate strikes at the very heart of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a precedent that could go way beyond this one case.

“It’s very, very rare for the Supreme Court to save a law that’s held to be discriminatory,” says Goldwater. “The Chief Justice’s justification for that is Quebec, being Quebec, is free to discriminate.

“This leaves constitutional law in an unexpected tension: As long as a provincial government wants to discriminate, it now appears to be free to do so. This is an intolerable proposition that nobody has actually noticed or commented upon.”

Goldwater argues that Eric v Lola turns the clock back to 1995, the year of the problematic Egan case. That’s when the Supreme Court ruled that denying Old Age Security spousal benefits to a gay couple was discriminatory — the first time that sexual orientation was read into the Charter's anti-discriminaion clause — but that the discrimination was allowed under Section 1. That’s why Goldwater finds Eric V Lola so disturbing. It’s as if Vriend never happened. In that 1998 case the Supreme Court ruled that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation could not be justified under Section 1 of the Charter, a key decision en route to securing same-sex marriage.

“Vriend is one of the most important cases ever written,” says Goldwater. “When Alberta discriminated against gays by deliberately refusing to protect them in Vriend, the Supreme Court had a fit and blasted Alberta. But in Eric v Lola, where Quebec discriminated against common-law couples by deliberately refusing to protect them, the Supreme Court handed them a cigar.

“It’s like throwing constitutional law back like 20 years.”

Goldwater uses terms like “politicized” and Quebec “appeasement” to criticize the Chief Justice’s ruling. “If the Chief Justice has just changed constitutional law in Canada as we know it, I think a majority of judges should say so in the next judgment. Let’s say there has been a delicate wish to avoid offending Quebec, which is something I find unacceptable.

“If the Supreme Court feels that federalism means that everybody has to bow to Quebec’s will, but Quebec has no obligation to cooperate with the rest of Canada, I’m scared for Confederation. I think the Supreme Court owes it to the population to say what the status of Quebec is in Confederation. Are we subject to the Charter anymore or not? I think it’s a pretty critical question.”

The fact that the question has been raised in a family law case is particularly significant for gay men and lesbians across Canada.

One of the reasons we have same-sex marriage federally is that as common-law couples won certain protections courts found it wrong to exclude same-sex couples from those protections. Common-law and same-sex relationships are linked, historically and legally.

“For the longest time, common-law relationships and same-sex relationships were being tested in the courts and were advancing kind of in lockstep as discriminated minorities, in fits and starts, lurching forward,” Goldwater says. She is uniquely positioned to understand that dynamic. Not only is she a leading advocate for the rights of women and mothers in common-law relationships, she and Dubé represented Hendricks and Leboeuf in the 2002 landmark ruling that won same-sex marriage in Quebec.

For observers like Goldwater and Jordan, now that the same-sex marriage fight has been won federally, it seems as if the Supreme Court is pulling up the drawbridge around the institution and leaving common-law couples and other non-traditional families out in the cold.

“I’m worried on a much broader level for the Supreme Court,” says Goldwater. “For lawyers interested in constitutional law, we have the feeling, and it’s very subjective of course, that the Supreme Court seems to be turning away from the liberal tendencies it used to have in the late ’80s and ’90s, which was really pro-Charter litigation. We seem to be in a new era of unexplained timidity.”

That means Charter challenges in family law may be out of bounds in the short to medium term. Future changes — which will need to address everything from assisted reproduction, surrogacy for gay fathers and multiple parents to the application of federal child support guidelines — will have to originate with provincial legislatures and new statues, not the courts. How that will proceed is anyone’s guess. When the Eric v Lola ruling came down, Quebec’s justice minister Bertrand St-Arnaud said the government was open to changing the laws to recognize the rights of common-law spouses. But then came a backlash and the government seems to be backpedaling.

While the wider implications of Eric v Lola remain uncertain, the ruling immediately impacts the relationships of 1.2 million people in Quebec. It also spotlights that common-law couples across the country — despite what they themselves may think — may not hold the same status as their married counterparts. And for all the media attention heaped on same-sex marriage, the vast majority of gay and lesbian couples in Canada are common-law. StatsCan’s latest findings on families show that while the number of same-sex marriages tripled between 2006 and 2011, same-sex common-law couples still outnumber same-sex married couples by more than two to one.

Only in BC (as of this month), Manitoba and Saskatchewan are common-law and married couples treated virtually the same, as well as in areas under federal jurisdictions, like income tax and Old Age Security. The rest is a patchwork, province to province. Confusion reigns.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there,” says Jordan. “A lot of people think they’re common-law after six months to a year. People tend to assume that they have an interest in the home after they’ve been together for so long. But it’s not true. I hear all kinds of things.”

The ruling in Eric v Lola brought to a close an 11-year legal odyssey. (There’s a publication ban in Canada on the parties’ real names. They’re easily found online, however; after all, how many billionaires are there in Quebec?) After meeting in Lola’s home country of Brazil when she was 17, Eric and Lola dated on and off for a few years. Later moving to Quebec, Lola lived with Eric for seven years, during which time they had three children. Lola wanted to get married; Eric didn’t, stating he didn’t believe in it. They broke up in 2002. Lola had custody of the children and Eric agreed to pay child support (and they came to their own agreement on access to the family home). But Lola also claimed spousal support and a share of Eric’s property, filing notice of a Charter challenge that argued de facto spouses (the legal term for common-law couples in Quebec, or conjoints de fait) should have the same rights as married couples when they split. The Quebec Superior Court denied her constitutional claims but the Quebec Court of Appeal allowed her claim for spousal support. That’s the ruling the Supreme Court overturned.

“There are 1.2 million people living common-law in the province of Quebec, about one half of them are presumed to be women, more or less, and they’ve just been left high and dry by the Supreme Court. No protection at all,” says Goldwater. “People almost passed out when they heard the decision. Nobody, but nobody, thought that would be the judgment.”

“I don’t know why we would protect vulnerable spouses who are married and not protect vulnerable spouses who are not married,” says Jordan. “I think as a society as a whole we should protect economically disadvantaged spouses upon dissolution of their relationship, particularly where there are children. That’s what’s so egregious about the facts in the Eric and Lola case.

“For those of us who do family law in the trenches, it’s a really hard decision to swallow,” says Jordan. “It’s one thing on the property, but on the spousal support? It’s just really hard.”

The irony lost on no one is that the ruling comes out of Quebec, where there are more common-law couples than anywhere else in the world. In Quebec, 31.4 percent of all families are common-law (compared to 16.7 percent nationally), and the number is growing.

“Women are in a very vulnerable position in Quebec,” says Jordan. “It’s the only province or territory that doesn’t have spousal support for common-law couples. So they’re really way out there. It’s antiquated.”

In her decision, Chief Justice McLachlin wrote that Quebec’s legal framework was designed “to promote choice and autonomy for all Quebec spouses. “Those who choose to marry choose the protections — but also the responsibilities — associated with that status. Those who choose not to marry avoid these state-imposed responsibilities and protections.”

Critics of the decision argue that choice in common-law relationships often resides solely with the wealthier party. People often stumble into such relationships; sometimes a disadvantaged partner can’t insist on a marriage. As Justice Rosalie Abella wrote in her dissenting opinion, “The decision to live together as unmarried spouses may, for some, not in fact be a choice at all.”

“I don’t think people choose to marry or not to marry based on wanting to enter into a certain legal set of rights and obligations,” says Jordan. “They don’t even understand the difference between common-law and married couples. So I don’t buy this choice argument.”

Whether it was an unmarried woman living and working on her male partner’s farm or a male couple paying into the Canada Pension Plan, case after case outside of Quebec recognized these relationships as marriages in all but name.

“This is the standard in the rest of Canada: You don’t look at whether a couple has gone to a city hall or a church to start their conjugal life. You look at the functional nature of the relationship. If it’s a conjugal, familial relationship, similar to marriage, then you recognize it as such,” says Goldwater.

Or as Abella, the only justice on the Supreme Court with a family law background, wrote in her dissent, “As the history of modern family law demonstrates, fairness requires that we look at the content of the relationship’s social package, not at how it is wrapped.”

But in most parts of Canada, despite winning increasing protections, common-law relationships are still not completely equivalent to marriage. In Ontario, for example, the big disadvantage for common-law couples is in property sharing and estates. Both married and common-law spouses are entitled to spousal support if the relationship breaks down (though only after the three-year time period required to establish a common-law relationship). But only married spouses share equally property accumulated during the marriage. The same holds if your partner dies. If you are not married, you have no automatic claim against your partner’s estate, no matter how long you’ve lived together or even if you have children together.

If you are in a common-law relationship in Ontario, write a will, otherwise you’re leaving your partner in a potentially awful financial and emotional bind. For the immediate future, it seems, even a Charter challenge can’t undo that bind.

LGBT activism has forced huge changes in Canadian family law. But despite the profound victory on same-sex marriage, those battles could be far from over. It will be fascinating to see how LGBT activists might affect those changes in the future. •