'Dancing, Prancing Boy'

BOOKS: Vivek Shraya comes of age on the banks of the North Saskatchewan

In Toronto, September 2014

He was an effeminate brown-skinned youth growing up on the Canadian prairies, clueless as to how others perceived him. At school he was called gay or faggot every day. At first he was bursting with music, eager to belt out a pop song by some reigning diva. Later he withdrew, a stranger to the world and to his own body.

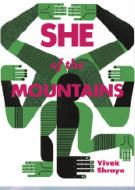

This description applies both to multidisciplinary artist Vivek Shraya as a teenager and to an unnamed protagonist in Shraya’s spirited debut novel She of the Mountains. The book presents a fictionalized account of Shraya’s journey towards love and self-acceptance; the overall trajectory is the same, only certain details have changed. For example, Shraya didn’t sing Vanessa Williams’ “Save the Best for Last” at an awkward school assembly like his protagonist did; Shraya sang “A Whole New World” by Peabo Bryson and Regina Belle.

It comes as a shock that Shraya, now 33, was so hectored as a teenager that he considered suicide. The handsome author, musician and filmmaker is as prodigious in personality as he is in talent. Recent projects include Breathe Again, a CD of Babyface covers, the short film Holy Mother My Mother, and What I Love about Being Queer, a film that morphed into a book and ongoing web project. In 2010 Shraya self-published a wonderful story collection God Loves Hair, a Lambda Literary Award finalist (and picked up this year by Arsenal Pulp Press, publisher of She of the Mountains). He’s been artist in residence at Camp Fyrefly, an LGBT youth retreat in Edmonton, facilitated Toronto’s queer youth writing group Pink Ink, and is currently coordinator of George Brown’s Positive Space program.

“As an adult I’ve tried to do all the things that could have made a difference to myself growing up,” says Shraya. “I’m always thinking about little Vivek and what he could have used or needed in some way.”

She of the Mountains is comprised of parallel love stories: One begins in 1990s Edmonton, where Shraya grew up; the other details the epic love between Hindu gods Shiva and Parvati. How audacious: Letting loose the Indian pantheon along the North Saskatchewan River.

“I felt I couldn’t write a love story without talking about hate, the experience of hate I’ve had,” says Shraya. “I also felt I couldn’t write a love story without talking about my relationship to my body. And that’s where the Hindu mythology came in because I grew up with all these fantastical gods. I mean there’s a god born out of someone’s nose; there’s a god who comes out of somebody’s belly button; Ganesha gets his head chopped off. There are these epic stories of how gods relate to their own bodies or how their bodies are created. And so it became an interesting counterpoint to exploring my own relationship to my body.”

The contemporary story follows a young man, who identifies as gay, as he falls in love with a woman. The couple’s passionate, tumultuous relationship begins before the man has had sex with another man and continues well after he starts. “That too is autobiographical,” says Shraya, who now identifies as queer. “I needed to address my experience with bi-phobia, coming from both the straight and gay community.”

Together, he and she, the unnamed lovers in She of the Mountains, are humble in the face of their undeniable attraction. Their love is bigger than any label and stronger than people’s hostility and confusion. Their emotional wisdom is inspiring. Theirs too is an epic love, and Shraya’s lyrical, quixotic writing makes palpable the profound physical and spiritual connection. Epic is a good word, here, for the book reads like two long prose poems intertwined, two epics fashioned into a double helix. No wonder DNA is the book’s opening motif (and one of the book’s many evocative illustrations by Raymond Biesinger). “In the beginning there is no he. There is no she,” it begins. “Two cells make up one cell. This is the mathematics behind creation. One plus one makes one.”

Finding unity in life’s basic binary is a uniquely queer project that continues to motivate the peripatetic Shraya. It’s also at the heart of Hindu teachings.

“I grew up in a non-denominational organization that was primarily Hindu-based. Though we celebrated Christmas, we celebrated Buddha’s birthday, the primary practices were very Hindu,” says Shraya. “That space was the only protected space I had growing up because in a Hindu context being a dancing, prancing boy wasn’t a negative. People thought I was God’s child, that I was like Krishna. I definitely had a huge connection to Hinduism growing up and a huge connection to the religious spark growing up. So it’s something that plays out in my work in different ways.”

That religious connection allowed Shraya to follow his first love, music.

“I always sang at the religious organization. I think I did a talk one day and I included snippets of pop songs, like REM and TLC and all these people. Somebody came up to me afterward and I asked if I had wrote those songs. And it never occurred to me that I could. After that I decided to try and do this thing, write my own songs. From 13 onwards I started writing my own stuff.

“That’s why I moved to Toronto, to pursue a musical career. That was back in 2003, pre-MySpace, pre-MP3. If you wanted to have a career in music you had to live in Toronto, that’s what everyone around me said.”

Though he studied English literature at university, Shraya’s burgeoning literary career happened by accident.

“I took one creative writing class for credit in university and my teacher lectured me for an hour about how I was a terrible writer and if anyone needed his class it was me. I really hated his class so I stopped going.

In Toronto, September 2014

He was an effeminate brown-skinned youth growing up on the Canadian prairies, clueless as to how others perceived him. At school he was called gay or faggot every day. At first he was bursting with music, eager to belt out a pop song by some reigning diva. Later he withdrew, a stranger to the world and to his own body.

This description applies both to multidisciplinary artist Vivek Shraya as a teenager and to an unnamed protagonist in Shraya’s spirited debut novel She of the Mountains. The book presents a fictionalized account of Shraya’s journey towards love and self-acceptance; the overall trajectory is the same, only certain details have changed. For example, Shraya didn’t sing Vanessa Williams’ “Save the Best for Last” at an awkward school assembly like his protagonist did; Shraya sang “A Whole New World” by Peabo Bryson and Regina Belle.

It comes as a shock that Shraya, now 33, was so hectored as a teenager that he considered suicide. The handsome author, musician and filmmaker is as prodigious in personality as he is in talent. Recent projects include Breathe Again, a CD of Babyface covers, the short film Holy Mother My Mother, and What I Love about Being Queer, a film that morphed into a book and ongoing web project. In 2010 Shraya self-published a wonderful story collection God Loves Hair, a Lambda Literary Award finalist (and picked up this year by Arsenal Pulp Press, publisher of She of the Mountains). He’s been artist in residence at Camp Fyrefly, an LGBT youth retreat in Edmonton, facilitated Toronto’s queer youth writing group Pink Ink, and is currently coordinator of George Brown’s Positive Space program.

“As an adult I’ve tried to do all the things that could have made a difference to myself growing up,” says Shraya. “I’m always thinking about little Vivek and what he could have used or needed in some way.”

She of the Mountains is comprised of parallel love stories: One begins in 1990s Edmonton, where Shraya grew up; the other details the epic love between Hindu gods Shiva and Parvati. How audacious: Letting loose the Indian pantheon along the North Saskatchewan River.

“I felt I couldn’t write a love story without talking about hate, the experience of hate I’ve had,” says Shraya. “I also felt I couldn’t write a love story without talking about my relationship to my body. And that’s where the Hindu mythology came in because I grew up with all these fantastical gods. I mean there’s a god born out of someone’s nose; there’s a god who comes out of somebody’s belly button; Ganesha gets his head chopped off. There are these epic stories of how gods relate to their own bodies or how their bodies are created. And so it became an interesting counterpoint to exploring my own relationship to my body.”

The contemporary story follows a young man, who identifies as gay, as he falls in love with a woman. The couple’s passionate, tumultuous relationship begins before the man has had sex with another man and continues well after he starts. “That too is autobiographical,” says Shraya, who now identifies as queer. “I needed to address my experience with bi-phobia, coming from both the straight and gay community.”

Together, he and she, the unnamed lovers in She of the Mountains, are humble in the face of their undeniable attraction. Their love is bigger than any label and stronger than people’s hostility and confusion. Their emotional wisdom is inspiring. Theirs too is an epic love, and Shraya’s lyrical, quixotic writing makes palpable the profound physical and spiritual connection. Epic is a good word, here, for the book reads like two long prose poems intertwined, two epics fashioned into a double helix. No wonder DNA is the book’s opening motif (and one of the book’s many evocative illustrations by Raymond Biesinger). “In the beginning there is no he. There is no she,” it begins. “Two cells make up one cell. This is the mathematics behind creation. One plus one makes one.”

Finding unity in life’s basic binary is a uniquely queer project that continues to motivate the peripatetic Shraya. It’s also at the heart of Hindu teachings.

“I grew up in a non-denominational organization that was primarily Hindu-based. Though we celebrated Christmas, we celebrated Buddha’s birthday, the primary practices were very Hindu,” says Shraya. “That space was the only protected space I had growing up because in a Hindu context being a dancing, prancing boy wasn’t a negative. People thought I was God’s child, that I was like Krishna. I definitely had a huge connection to Hinduism growing up and a huge connection to the religious spark growing up. So it’s something that plays out in my work in different ways.”

That religious connection allowed Shraya to follow his first love, music.

“I always sang at the religious organization. I think I did a talk one day and I included snippets of pop songs, like REM and TLC and all these people. Somebody came up to me afterward and I asked if I had wrote those songs. And it never occurred to me that I could. After that I decided to try and do this thing, write my own songs. From 13 onwards I started writing my own stuff.

“That’s why I moved to Toronto, to pursue a musical career. That was back in 2003, pre-MySpace, pre-MP3. If you wanted to have a career in music you had to live in Toronto, that’s what everyone around me said.”

Though he studied English literature at university, Shraya’s burgeoning literary career happened by accident.

“I took one creative writing class for credit in university and my teacher lectured me for an hour about how I was a terrible writer and if anyone needed his class it was me. I really hated his class so I stopped going.

|

“I didn’t really come back to writing outside of music until six years ago, mostly because I was on a label overseas for a while and they kept shelving my [music] projects…. I got really frustrated so I started writing these journal entries that eventually grew into God Loves Hair. It was just this innocent little side project, but the response was, ‘Wow.’ I thought maybe there are more stories I want to talk about, more stories I want to share.”

And where does the epic quality of the writing come from? Shraya writes lyrics, but does he write poetry? “No, I don’t write poetry,” he says. “But when I started God Loves Hair, a friend read an early draft and said, ‘Where’s the music?’ I think that was an important moment for me. ‘Oh, right. Of course, there should be musicality to it.’” There’s plenty of music, beautiful and heartbreaking, in She of the Mountains, Shraya’s irresistible invitation to join the cosmic dance. SHE OF THE MOUNTAINS By Vivek Shraya. Arsenal Pulp Press. Toronto launch. 7pm. Wed, Sep 17. Gladstone Hotel. 1214 Queen St W. arsenalpulp.com. |