Waving a Batik Flag

A few thoughts on heritage, culture and our hybridized existence

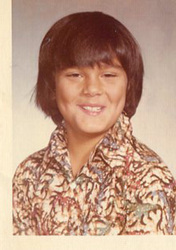

When I was very young, I mistakenly thought I was quarter Chinese. Can you blame me? I mean, look at me (above; age seven, I think). Part of the confusion stemmed from being born in predominantly Chinese Singapore and being mixed-race; what my mother called Eurasian, her Rs rolling to the horizon. Currently Singapore is about 73 percent Chinese, 13 percent Malay and 9 percent Indian. My mother is Indian and her family goes back untold generations in what was formerly known as Malaya; my father is English. So I thought I was half Indian, half English and a quarter Chinese -- and math would later be my best subject. It was all those fractions and percentages. Plus I had Chinese aunts and half-Chinese cousins... and, well, look at me.

Ever since I was that mixed-up mixed-race kid, I've loved batik. It's my heritage. Even though my family moved to Winnipeg when I was still a baby, I must be wearing a batik shirt in a third of all my school photos. After my father died in 1999, I got a bunch of his batiks; most of the swatches above are from his shirts. (This sample doesn't even scratch the surface of the shirts I've owned over the years, let alone the sarongs and other items in my possession. There's a custom batik suit jacket that deserves its own post.) All but the satin shirt above date back to the early 1960s, from before we moved to Canada. I loved these older shirts most of all, so soft, such crazy patterns. I could never decide which was my favourite... though that spider, web and flower pattern with the Raffles label was something special. Sadly the shirts all fell apart from overuse. I gave the remnants to my friend, textile artist Grant Heaps, in the hope that they might live again in some other guise.

As most people know, traditionally, batik is made by a wax resist dyeing technique. Wax patterns are drawn or stamped onto the fabric before it's dyed; the dye won't show wherever there's wax. Complex patterns are built up by adding and removing layers of wax patterning before each colour bath. To me it's a perfect symbol of my syncretic heritage, how immigrants of all backgrounds cherry pick and discard various elements from our cultures of birth and adoption, building something new and whole by layering additions and subtractions. But that's what everyone does, not just immigrants and culturally hyphenated folks, especially in our increasingly connected world. No culture develops in isolation.

While the technique may have originally come from India, batik dates back to at least the 12th-century in Java where it reached its pinnacle; it may very well have developed indigenously in parts of what is now Indonesia. Today, it's made throughout southeast Asia. I've been to some amazing batik factories in northeast Malaysia. But the history is quite contested. When the UN added Indonesian batik to its list of the "Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity" in 2009 it flamed a culture war between Malaysia and Indonesia. Indonesians complained that Malaysians had "stolen" batik; that they had no claim to it. (It should be noted that the two countries share commonalities and rivalries much in the same way that Canada and the US do, though over a considerably much longer time frame; only siblings fight like this.) But claims to exclusivity are anathema to southeast Asia, a maritime region that, until fairly recently, enjoyed the free movement of people, trade goods and ideas. Exclusivity does not wear batik. As the UNESCO website notes, batik contains everything from Arabic calligraphy and European florals to Chinese phoenixes, Japanese cherry blossoms and Indo-Persian peacocks.

So my claim to batik does not stem from my Malaysianess, regardless of what some Indonesians might think, nor does it stem from some other unique racial or cultural connection. I strongly believe that everyone has equal claim to all cultures. There is no such thing as misappropriation -- there is such a thing as facile understanding or inept art, but that should never preclude the attempted connection. Like with music, like with food, mixing things up makes for beautiful, meaningful creations. World cultures are the heritage of us all. We all live under a batik flag.

Ever since I was that mixed-up mixed-race kid, I've loved batik. It's my heritage. Even though my family moved to Winnipeg when I was still a baby, I must be wearing a batik shirt in a third of all my school photos. After my father died in 1999, I got a bunch of his batiks; most of the swatches above are from his shirts. (This sample doesn't even scratch the surface of the shirts I've owned over the years, let alone the sarongs and other items in my possession. There's a custom batik suit jacket that deserves its own post.) All but the satin shirt above date back to the early 1960s, from before we moved to Canada. I loved these older shirts most of all, so soft, such crazy patterns. I could never decide which was my favourite... though that spider, web and flower pattern with the Raffles label was something special. Sadly the shirts all fell apart from overuse. I gave the remnants to my friend, textile artist Grant Heaps, in the hope that they might live again in some other guise.

As most people know, traditionally, batik is made by a wax resist dyeing technique. Wax patterns are drawn or stamped onto the fabric before it's dyed; the dye won't show wherever there's wax. Complex patterns are built up by adding and removing layers of wax patterning before each colour bath. To me it's a perfect symbol of my syncretic heritage, how immigrants of all backgrounds cherry pick and discard various elements from our cultures of birth and adoption, building something new and whole by layering additions and subtractions. But that's what everyone does, not just immigrants and culturally hyphenated folks, especially in our increasingly connected world. No culture develops in isolation.

While the technique may have originally come from India, batik dates back to at least the 12th-century in Java where it reached its pinnacle; it may very well have developed indigenously in parts of what is now Indonesia. Today, it's made throughout southeast Asia. I've been to some amazing batik factories in northeast Malaysia. But the history is quite contested. When the UN added Indonesian batik to its list of the "Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity" in 2009 it flamed a culture war between Malaysia and Indonesia. Indonesians complained that Malaysians had "stolen" batik; that they had no claim to it. (It should be noted that the two countries share commonalities and rivalries much in the same way that Canada and the US do, though over a considerably much longer time frame; only siblings fight like this.) But claims to exclusivity are anathema to southeast Asia, a maritime region that, until fairly recently, enjoyed the free movement of people, trade goods and ideas. Exclusivity does not wear batik. As the UNESCO website notes, batik contains everything from Arabic calligraphy and European florals to Chinese phoenixes, Japanese cherry blossoms and Indo-Persian peacocks.

So my claim to batik does not stem from my Malaysianess, regardless of what some Indonesians might think, nor does it stem from some other unique racial or cultural connection. I strongly believe that everyone has equal claim to all cultures. There is no such thing as misappropriation -- there is such a thing as facile understanding or inept art, but that should never preclude the attempted connection. Like with music, like with food, mixing things up makes for beautiful, meaningful creations. World cultures are the heritage of us all. We all live under a batik flag.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed